BLOG

Black Popular Culture Scholar, Dance Educator, Choreographer

Halifu Osumare | BLOG

By Halifu Osumare

•

June 4, 2023

"50 Years of Hip Hop" is a radio show on Timeout Youth radio in Davis California, for which I was interviewed about my dance career and my hip-hop scholarship (about 7 minutes into the show). It is produced by Rohan Baxi, a 16 year old high school student in Davis. It is very well researched and produced, showing the Gen Z generation and the one coming afterward are doing relevant work. Check out the radio show at: https://kdrt.org/audio/70-50-years-hip-hop

By Halifu Osumare

•

March 27, 2021

There is something about this time, about this nowness that drives me; it ignites me [as] a Pan-African pursuit of Liberation. This could be defined as Social Change; it is most certainly a shifting paradigm . — Marjani Fortè-Saunders “There is something about this time,” dance artist Marjani Fortè-Saunders asserts, that harkens to the past, while simultaneously pointing us toward the future. I initiate this article on three phenomenal Black women dance artists by situating the four of us in a historical continuum of Amer- ican dance and “shifting paradigms” in the United States. I cannot be the objective authority on dance and Black choreographers; I must acknowledge my dancing voice in an activist lineage, which includes these three probing dance artists as current incarnations of a collective embodied liberation movement. Each of us represents a nexus on the historical lineage of Black dancing bodies seeking personal freedom while choreographing collective social change. I am a baby boomer from the activist San Francisco- Oakland Bay Area, who helped initiate dance as a medium of social change in the revolutionary late- 1960s, a generation that turned to Africa as a distinguishing element in our Black dance forms during our era’s Black Arts Movement. Amara Tabor-Smith, also from the Bay Area but of Generation X, pushed our work further with an increased understand- ing of African spirituality. Millennials Marjani Fortè-Saunders in Pasadena, Calif., and Jennifer Harge in Detroit approach social activism through dance utilizing internal probing, lodged in collective Black memory. Each of us are products of our time and generation. These three dance artists produce process-oriented performance in relation to their defined communities. Here, I explore their common aesthetic and metaphysical threads, while exposing their unique performative approaches. Black Radical Performance Each artist is engaged in uncompromising revolutionary performance work in the Black tradition. Marjani’s nomenclature of “Radical Black Performance” best captures the nature of their collective interrogation of the Black experience, past, present, and futuristically. At one level, their performance is radical because, rather than privileging themselves, each employs a communal methodology centering the community with which they engage. Philosophically, this choice emerges from an Africanist aesthetic characterized by individual invention that evolved out of a collectivist tradition; each artist’s vision is in dialogue with communal practices that grow over time through ongoing improvisation between vision and practice. Product — choreography or finished presentational work— takes a back seat to this open-ended process with community. Jennifer explains: “I’m constructing a somatic approach that is less concerned with western dance fluency, and more committed to a physical experience an- chored in Black interiority. I believe that Black Womxn and our bodies re- tain and uphold a breadth of narratives that are able to teach about histories of oppression and how we may continue to resist capture.” One can see this approach in her 2019 work FLY | DROWN, an installation piece focused on her grandparents’ migration from Tennessee to Detroit, interrogating how one makes home after leaving all that one knows. As Jennifer works through this dilemma in her own spirit, she reveals embodied exigencies of the Great Black Migration from the south to the north a century ago, from an internal perspective, rather than a polemic, as it might have in choreographies of earlier artists. Marjani has a similar philosophical approach to her movement explorations. She reflects on her process within her lineage: “I am merely a link in my generation’s chain of sorcerers, all imagining a liberation we’ve never known, and pursuing it ceaselessly through the bounty of our crafts.” She avails her- self to many Black crafts, intellectuals, and artists that inform her work, like philosopher and poet Fred Moten, author James Baldwin, pianist/composer Cecil Taylor, and choreographers Bill T. Jones and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar. The collaborative ensemble Marjani formed with her husband, musician/composer Everett Saunders, called 7NMS/Prophet, embraces the tagline: “The two tote a revolutionary commitment of art and performance as a ministry of liberation.” Amara, in northern California, is known for her large site-specific dance-theater performances driven by a community that includes ancestors. Her 2013 work He Moved Swiftly But Gently Down The Not Too Crowded of oppression and how we may continue to resist capture.” One can see this approach in her 2019 work FLY | DROWN, an installation piece focused on her grandparents’ migration from Tennessee to Detroit, interrogating how one makes home after leaving all that one knows. As Jennifer works through this dilemma in her own spirit, she reveals embodied exigencies of the Great Black Migration from the south to the north a century ago, from an internal perspective, rather than a polemic, as it might have in choreographies of earlier artists. Marjani has a similar philosophical approach to her movement explorations. She reflects on her process within her lineage: “I am merely a link in my generation’s chain of sorcerers, all imagining a liberation we’ve never known, and pursuing it ceaselessly through the bounty of our crafts.” She avails her- self to many Black crafts, intellectuals, and artists that inform her work, like philosopher and poet Fred Moten, author James Baldwin, pianist/composer Cecil Taylor, and choreographers Bill T. Jones and Jawole Willa Jo Zollar.The collaborative ensemble Marjani formed with her husband, musician/composer Everett Saunders, called 7NMS/Prophet, embraces the tagline: “The two tote a revolutionary commitment of art and performance as a ministry of liberation.” Amara, in northern California, is known for her large site-specific dance-theater performances driven by a community that includes ancestors. Her 2013 work He Moved Swiftly But Gently Down The Not Too Crowded Street was a tribute to San Francisco dancer/choreographer Ed Mock, who died in 1986, one of the region’s first AIDS victims. Mock was an important dancer/choreographer in San Francisco since the 1960s, and Amara joined his company; hence, she was “called” to create a work in tribute to him. The work was created within the larger context of gentrification and the city’s loss of many of its Black men. The 25 dancers per- formed in several outdoor settings throughout the city, including in front of Mock’s studio at 32 Page Street. As an initiated Yoruba priestess, Amara’s improvisational conversation with community often engages the dead, as in the case of He Moved Swiftly .... “The integration of my spiritual practice in my art making was influenced by my ancestors who kept com- municating to me that it was time to do so,” she says. “I made a decision to get out of the way and listen to them.” As a result, she calls her aesthetic “Afro Surrealist Conjure Art.” A second level of these artists’ Black Radical Performance is community engage- ment for social change, lodged squarely in socio-political activism. Amara’s 2019 House/Full of Black Women grew out of her partnership with Oakland’s MISSEY and with sex-trafficking abolitionist Regina Evans of Regina’s door, organizations that combat sex trafficking of youth. After anti-trafficking training, in 2015 Amara gathered a group of “20 Black women performers [into] activities that specifically address the issues of displacement, well-being, and the sex trafficking of Black women/femmes and girls in Oakland.” Her community of Black women performers made a five-year commitment to develop a process that engenders ritual performance episodes. Situated at various outdoor Oakland sites, the work often uses Egungun (ancestor) masquerade, based in Nigerian, Beninese, and Brazilian traditions. Amara’s adept creative process tapped a vital community social need and her performers’ communal performative process comingled in a ritual for social change. Marjani, along with Everett, created Art & Power, a platform and organization dedicated to Black wellness and innovation. Art & Power is multi-dimensional: “modeling collective action, spiritual transcendence, cross-sector engagement, and inheritance.” Marjani was a child schooled in Africanist alternative educational institutions by parents influenced by my generations’ Black Power and Black Arts Movements. Her resulting activist vision was reinforced by dancing with Jawole Willa Jo Zollar’s Urban Bush Women (UBW), which focused on community engagement as choreo- graphic process. As a lead facilitator (2007-2012) with UBW in cities where the company established long-term residences, she worked to bridge perfor- mance with community development. Amara, too, is underpinned by the UBW experience, having worked as its associate artistic director from 2004 to 2006. Now in southern California, Marjani has maintained a bi-coastal career, both artistically and politically, traveling between New York and Cal- ifornia for many years. Art & Power promises to be an important institution for personal artistic innovation and Black community advancement. Jennifer takes a personal approach to her activ- ism: “Social change in my practice looks like giving myself permission to create in ways that prioritize my full being, so it is super Black, it’s queer-affirming, and it’s slow, meaning I give myself agency to stay inside of creative ideas for long periods of time.” In her company, Harge Dance Stories, she chooses Black women “skilled with shifting course and practicing refusal, with a focus on personal and community caretaking.” Jennifer locates collective Black liberation “on a cellular level” that is revealed in the “DNA of the gospel church, improvisation, big juicy lyrical phrases, and the architecture and brava- do of rap music.” Nowhere is this Black DNA more apparent than in her performance piece “mourn and never tire,” staged directly on the pulpit of the Washington National Cathedral, surrounded by the choir, pastor, and deacons of the Episcopal church. It is a tribute to those fallen young, unarmed Black people at the hand of police — Philando Castile, Sandra Bland, Oscar Grant, Tamir Rice, Michael Brown, George Floyd, and so many others. Dressed in a black leotard, long black chiffon skirt and tennis shoes, she runs in place at the podium mic — literally running for their lives — in front of church elders, all the while reading the names, ages, and places of the fallen. Jennifer, barefoot, segues into an emotional embodiment of grief, as many parishioners wipe the tears from their eyes. The mission of “mourn and never tire” is to “process Black Americans’ relationship to endurance, death, and ancestry,” she states. Her dance activism becomes a communal internal process: “I’m now working less capitalistic, less transactional, and less product-oriented. I’ve given myself permission to be in process.” This takes more time than merely choreo- graphing a new work. After centuries of slavery, segregation, public Black political action, her work is the spiritual interiority that today’s Black Lives Matter activism dictates. Black Radical Performance takes many forms. Physical Historians of Black interiority Noted hip-hop choreographer Rennie Harris has said that the best dancers are physical historians, bringing forth the past through the body. Jennifer, Amara, and Marjani are indeed dancemakers who chronicle and embody vital issues, past and present. They do so through delving into inner pathways that speak a 21st-century ontology. Finding the heart-center of a burning concern, in process with community, characterizes their internal methodologies for communal healing of past and present oppressions. These artists engage dancemaking that harkens back to ancient rituals, like slavery-era Ring Shouts — the sacred African dance circles reinvented as New World healing rituals. Their communal ceremonies, meditations, and therapeutic discussions form a “new” sacred methodology for community restoration. These three choreographers employ aspects of this Black interiority in their choreographic works. Marjani’s Memoirs of a . . .Unicorn premiered at New York’s Collapsible Hole in 2017, “weaves personal and historic narratives” that fiercely interrogate her father’s story as prologue to her internal inquiry. The work becomes research into “the [internal] properties of Black American magic and resilience.” Her father, storyteller Rick Fortè, built the pyramid set designed by Mimi Lien, and he opens the work perched atop the set, weaving a magical tale ultimately about survival as Black man with his daughter in America. Marjani enters carrying a pan of water — a biblical reference to Jesus — then she gently takes off the shoes and socks of another Black male in the audience, to humbly wash his feet. Breaking the fourth wall is another characteristic that binds these artists, often performing in ceremonial ways to lead viewers beyond passive observation into complicit participation. In Jennifer’s FLY | DROWN, the set is a personal installation of “domestic markers” — pink carpet, plastic runner, old-school console television — that triggers deep memories of her post-migration grandparents’ home. Wearing Hanes-style white cotton panties, a sports bra, and a crystal sequined headdress draping over her face like an African mask, her trance-like jerky movements travel through the set to Sterling Toles’ and Boldy James’ “Requiem for Bubz.” Black legacy manifests as an inward process of memory rather than outward melodrama. Through her Deep Waters Dance Theater, Amara presented several epi- sodes of her site-specific ritual performance House/Full of Black Women (2019) in downtown Oakland. Oaklanders on the street at night during one masquerade episode find the Black female performers, swathed in white long dresses, veiled, and carrying flora and fauna. They ritualistically parade among cars driven by the question, “How can we, as Black women and girls, find space to breathe, and be well within a stable home?” There is no fourth wall, no theatrical side wings nor backdrop of a proscenium theater or black box studio; the streets and random people become the stage and set. The onlookers are forced to react, decipher, and participate in addressing this vital women’s issue. These three artists confront us. They challenge us. They allow us an oppor- tunity to take an internal journey with them. We are asked to imagine our own excursion into legacy and the search for love in this moment, in this now. Cinematographer and visual artist Arthur Jafa poignantly pronounced: “Black folks are the first postmodern subjects,” and Marjani continues the idea by saying, “abstracted from our land and cultural rooting, yet imbued with an, arguably, divine, or celestial capacity, to re-define, to re-appropri- ate, to re-member, endlessly!” Marjani, Amara, and Jennifer are all probing embodied memory as a lens into the Afrofuture. For further information, please visit the artists’ websites: Marjani Fortè-Saunders , Amara Tabor-Smith and Jennifer Harge.

By Dr. Halifu Osumare

•

September 13, 2020

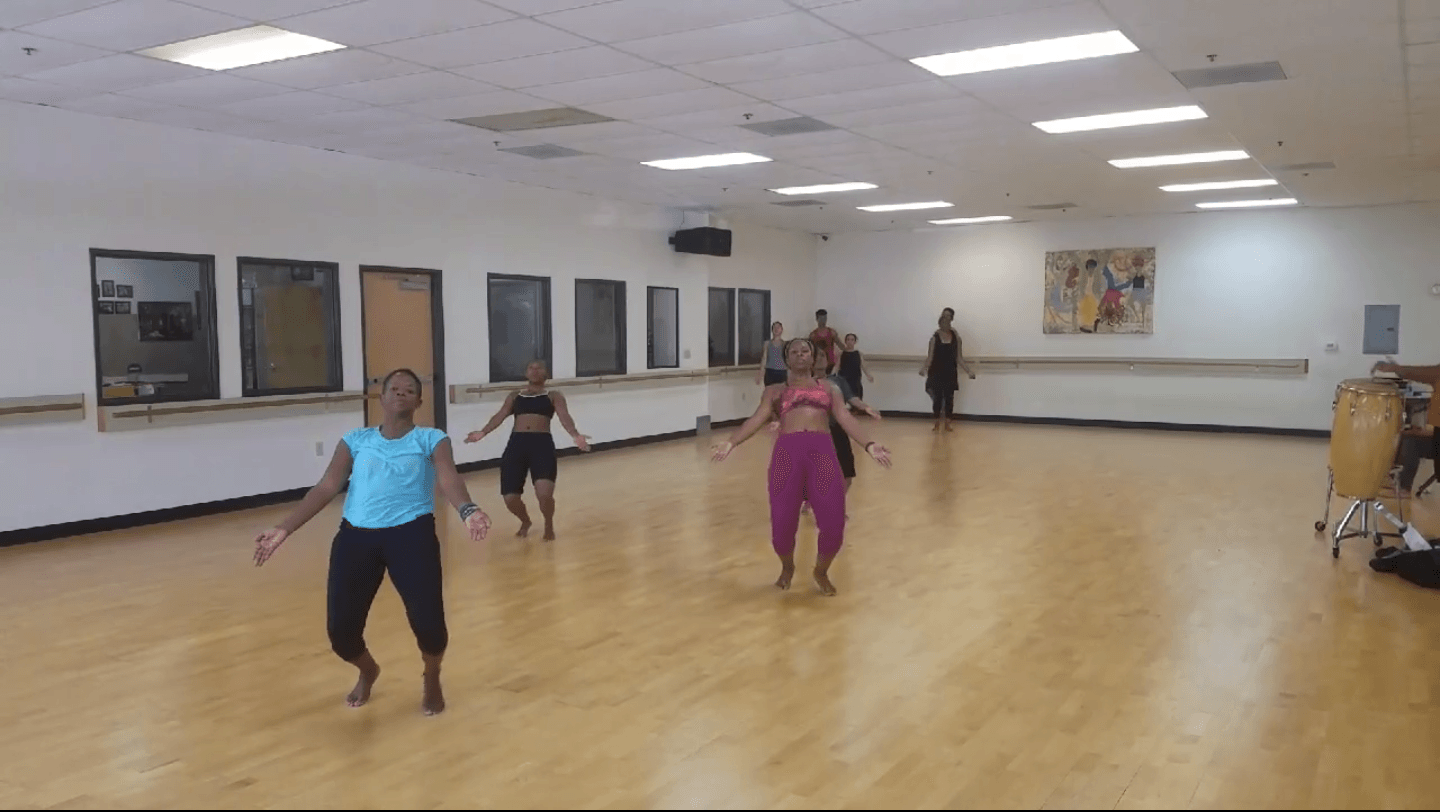

This video clip represents the culminating across-the-floor dance sequence I created for my Katherine Dunham Dance Technique class in Sacramento around 2018. As a Certified Dunham Instructor since 2001 and a life-long student of the Dunham Technique since 1966, I am proud of my continual learning process with what Madame Katherine Dunham (1909-2006) called “A Way of Life.” For Dunham Technique is just that, allowing the student to integrate mind, body, and spirit through the embodiment of knowledge of the Self. I’m sitting on the other side of our accompanying drummer, playing the agogo bell while the students show me what they have learned during my 6-week workshop. Some of the students are Ayo Walker, Windy Kahana, Miguel Forbes, Valerie Gnassounou-Bynoe, and Lance Casey, all of who have been affiliated with California State University, Sacramento as students or dancers. They have learned well the Afro-Caribbean modern dance sequence I have taught them based in Dunham Technique. There are typical Dunham phrases like Dunham walk and triplets, fall-recovery, second-cross-second-turn, and the ever-present torso isolations. They have learned well, representing my knowledge of the “The Way of Life” of Katherine the Great. Below is an short excerpt from an online essay I published in 2010 about Katherine Dunham and her dance technique: Dancing the Black Atlantic: Katherine Dunham’s Research-to-Performance Method Halifu Osumare (Article published in the special issue of AmeriQuest Vol. 7 No.1 (Spring 2010) ( http://www.ameriquests.org/index.php/ameriquests/article/view/165 ) Dancer-anthropologist Katherine Dunham was the first to research Caribbean dances and their socio-cultural contexts. From her seminal mid-1930s fieldwork she re-created specific Afro- Caribbean dances into creative ballets on western stages, thus creating a dynamic confluence between anthropology and dance. As one of the few African American anthropologists of that period, Dunham’s choreographic method and her published ethnographies reveal an erudite artist- scholar who was very aware that she was breaking new ground. Summarily, Dunham created performance ethnographies of the Caribbean on the world’s greatest stages, privileged the voices of her informants in her written ethnographies, and created staged visions of cross-cultural communication. In the process, she clearly envisioned the African diaspora–the Black Atlantic–long before that nomenclature was ever used. Although Paul Gilroy conceptualized the Black Atlantic as an “...intercultural and transnational formation...” in the 1990s (The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, 1993), Dunham implicitly understood and utilized this formation as both geographical and cultural in the 1930s, sixty years earlier. Her intellectual prescience illuminated crucial links between movement styles of African descendant peoples in the Americas and their overarching societies, revealing a legacy of creolized African culture in the Caribbean, the expressive dances and rhythms of which she wanted to dignify as important contributions to world culture. Special Note: I thank Dr. Ayo Walker for taping the Dunham progression and sharing it.

By Halifu Osumare

•

January 10, 2020

This dance collage was used as a part of "REVIVAL: Millennial remembering in the Afro Now" by Amara Tabor-Smith, November 14-16, 2019, Stanford University. It was a phenomenal performance art work in multiple venues inspired by the founding of the Committee On Black Performing Arts (CBPA), which I helped develop from 1981-1993. Utilizing the stories and characteristics of the Yoruba deities known as Orisa, REVIVAL is a multimedia and multi-site experience exploring the people and events that have catalyzed movement of for social change through time.

By Halifu Osumare

•

October 5, 2019

Drs. Brenda Dixon Gottschild and Halifu Osumare came together in a studio at University of California, Davis in 2016 to talk about their careers as dancers and dance scholars. As a result Contemporary Black Canvas created a podcast, as these two dance luminaries weigh in on the air waves. Listen up to the wisdom of these pioneering agents, sharing their unique perspectives about their beginnings in the 1960s Black Arts Movement on the East and West Coast: C lick Here to hear the Podcast

By Halifu Osumare

•

July 2, 2019

Choreographer: Halifu Osumare Assistant Choreographer: Miguel Forbes Rehearsal Assistant: Windy Kahana Art Photography: Marcus Gordon Music: Nicholas Britell –“Eden (Harlem)”; “Don’t Shoot” – The Game et al.; “Heaven All Around Me” – Saba; “DNA” – Kendrick Lamar Dancers: Miguel Forbes, Andrea Guianan, Taylor Hill, JAH’Sol Porras-White, Christopher Salango, Ni’Mat Laila Shabazz Videographer: Patrick Fitzgibbons Black and brown communities are under state terror, with police brutality and the killing of unarmed black men and women that is going unaccountable. “Resistance/Resilience” is about that terror and its psychological and spiritual impact on those communities. Resistance is what is necessary as manifested in the many Black Lives Matters demonstrations, and long-term spiritual resilience is what is necessary to survive and thrive in order to continue to resist.

By Halifu Osumare

•

April 16, 2019

With the Trump administration’s hardline and heartless immigration policies, starting with the 2017 rescinding of DACA (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals) for young immigrants already in the U.S. and continuing with the 2018 family separation policy under his so-called “zero-tolerance” approach at the U.S.-Mexico border, the focus has been on brown people escaping poverty, gang violence, and state terror in Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador. But there are also tens of thousands of African, Caribbean, and African diasporans entering the country by plane that are also trapped in the morass of Trumpian hardline immigration policies. I explored the more publicized Latino immigration issue in my previous blog “’Blackifying’ the Immigration Issue: DACA and the Black Community.” ( https://www.hosumare.com/blackifying-the-immigration-issue-daca-and-the-black-community ). However, more attention needs to be paid to black immigration and problems that African descendants face with the racist U.S. immigration policies. Three organizations lead the charge to help black immigrants in the fight against unfair U.S. immigration policies. The Undocublack Network ( http://undocublack.org ) was organized in 2016 to fight for immigrant rights and racial justice for black undocumented individuals. Then there is BAJI (Black Alliance for Just Immigration) that exists to counteract the racial profiling that leads to disproportionate rates of immigration detention and deportation among black people. With offices in four major black metropolitan areas---Atlanta, Los Angeles, Oakland, and Los Angeles---the BAJI website ( https://baji.org ) says, “black immigrants have the highest unemployment rates and earn the lowest wages, even though they are among the most educated.” Lastly, there is African Communities Together (ACT) that focuses specifically on Continental African immigrants who are victims of U.S. Immigration laws. Their website ( http://www.africans.us ) reveals that Africans “are as diverse as the African continent from which they come,” and “are at the heart of this organization.” One of their programs focuses on protecting the status for holders of Temporary Protected Status (TPS) from Somalia, Sudan, Guinea, Liberia, Sierra Leone, and South Sudan. The Undocublack Network is leading the 2019 efforts to keep Deferred Enforcement Departure (DED) status for Liberians, who were given Temporary Protected Status (TPS) in 1990 during the fourteen-year civil war in that country. Most Liberians in the U.S. have been here since the initiation of TPS. Many came as young children, the same as many Mexican and Latino/a DREAMERS, and haven’t been home in 30 years. The Trump administration’s hardline and bigoted immigration policy declared an end to DED for Liberians, leaving thousands of them facing deportation as of March 31, 2019. After the Liberian civil war and the devastating Ebola virus epidemic, Liberia as country is dealing with extreme poverty and a challenged health care system, with very limited employment opportunities. Therefore, there is not the infrastructure in Liberia to deal with thousands of Liberians being deported back to their country. As a result, a massive online campaign was initiated to get the Trump administration to extend DED by some of the aforementioned black immigration organizations. Even the American progressive public policy advocacy group MoveOn has joined the black immigration advocacy groups with an online campaign to promote congressional Bill H.R.6 to ensure extension of the status of Liberians. UndocuBlack Network and African Communities Together filed a lawsuit with the Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights against the Trump Administration for terminating DED. Yatta Kiazolu, a Liberian DED holder and a UCLA Ph.D. candidate, testified before the House Judiciary Committee, stating, “Considering the ways our lives have been tossed into upheaval, this lawsuit is a step toward restoring our humanity.” David Korma, another Liberian DED holder, testified to the personal toll of ending DED: “I worry everyday about my life. What am I going to do? I have been in America nineteen years. I joined this lawsuit for my six children; they are my family. Our dreams and hopes are here.” UndocuBlack Network summarizes the situation this way: “The lawsuit will demonstrate that the President’s termination of DED is racist, cruel and destructive to Liberians, their families, and communities.” These online, legal, and congressional efforts paid off, because on April 1 DED was extended for one year. Liberians’ advocacy efforts, in the face of losing their protected status, received support from several U.S. law makers, including Minnesota Attorney General Keith Ellison. Hennepin County, Minnesota, home to Minneapolis, has the greatest number of Liberians---an estimated 8,285, with 35,000 Liberians living in the entire state. Working in favor of Liberians living in the U.S., American international interests in Africa played an important part in the Trump administration’s decision to extend DED. The U.S. government’s official decision stated that, The overall situation in West Africa remains concerning, the extension decision said, and Liberia is an important regional partner for the Unit4ed States. Reintegration of the DED beneficiaries into Liberian civil and political life will be a complex task. And an unsuccessful transition could strain U.S.-Liberian relations and undermine Liberia’s post-civil war strides toward democracy and political stability. In general, black immigration organizations are becoming more politically savvy and reaching out to their constituency and connecting them to sympathetic congressional leaders. On February 23, BAJI hosted a “story circle” in New York City where black community members shared the realities of migration, rituals, tradition, and race, as part of the African diaspora living in that city, and Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez joined the circle. During the “story circle,” community members shared their personal narratives, and the resulting stories were documented and transcribed into zines that will be featured in a traveling newsstand. The African diaspora community is utilizing all resources at their disposal to spread their immigration messages in the era of increased bigoted U.S. immigration policy. Black Caribbean immigrants are also under fire in this immigration maelstrom. Philadelphia, as sanctuary city, is becoming home to immigrants trying to avoid deportation. One story that has emerged in that city is that of Clive and Oneita Thompson and family, who fled Jamaica to escape threats from gangs after Oneita’s brother was killed. They first moved to South New Jersey where they lived for fourteen years. But in September 2018 their visas expired, and in January 2019 they had to flee to First United Methodist Church in Philadelphia’s Germantown. Undocublack revealed that for years the entire Thompson family had frequently checked in with Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and filed a series of stays of removal. But those legal briefs ran out on August 31, 2018. The Thompsons then contacted the New Sanctuary Coalition in Pennsylvania, leaving their New Jersey home, their jobs, and their community to move to Philadelphia with their two U.S. citizen children, Christine and Timothy. They then started online advocacy with a petition of support and fundraising campaign. Undocublack makes it clear that in the current immigration climate, it is much easier to enter a sanctuary for asylum than to exit one, and the Thompson family continues to hold up in Philadelphia’s United Method Church. The immigration issue regarding the African diaspora can crop up in places where one would least expect it, and such was the case with ICE’s jailing of well-known Atlanta rapper 21 Savage. Most people did not know that She’yaa Bin Abraham-Joseph, popularly known as 21 Savage, was actually born in London in 1992 to British born parents of Dominican and Haitian descent. After his mother and father divorced, he moved with his mother to Atlanta at age seven. This is again a story of a young child being brought to the U.S. and growing up as an American. But, in this case the child became a celebrated rapper-songwriter-producer, with his second album “I Am > I Was” spending two weeks atop the Billboard Album chart. But a week before he was scheduled to perform on the 61st Grammys Award he was arrested by ICE for being a citizen of the United Kingdom who entered the U.S. in 2005 and unlawfully overstayed his visa that had expired a year later. According to music critic Jon Caramanica in a February 27 New York Times article, “His attorneys---Dina La Polt, his general counsel, and Charles Kuck, his immigration attorney—proposed that there might have been political motivations at play.” In fact, they say his arrest was based on lyrics denouncing the inhumane family separations at the Mexican border. In his extended version of his 2018 track “A Lot” he raps, “Went through some things, but I couldn’t imagine my kids stuck at the border/Flint still need water, niggahs was innocent, couldn’t get lawyers.” And, what’s more he performed “A Lot” on the Tonight Show with Jimmy Fallon in late January, and on February 3 ICE arrested him. Hence, it becomes obvious as an artist his freedom of speech was violated, with his detainment politically-motivated due to the Trump administration’s tendency to take revenge on anyone with a big platform who denounces his racist and inhumane immigration policies. Although he was released on February 13 on a $100,000 bond, during his detention a significant number of activist organizations galvanized around the #Free21Savage coalition. Subsequently, there is a Stop the Deportation of the She’Yaa Bin Abraham-Joseph movement created by Black Lives Matter movement Co-Founder Patrisse Khan-Cullors. She stated in a memo to ICE Field Office Director Sean Gallagher, “The U.S.’s violent history of criminalizing Blackness intersects with its deadly legacy of detaining and deporting Black and Brown immigrants. This needs to stop today!” She also stated an important statistic: 4.2 million black immigrants live in the U.S., with 619,000 undocumented. The immigration case of a celebrity like 21 Savage helps to galvanize black politicians, as well as the online activist community to take a stand on these unfair U.S. immigration policies and procedures. The Congressional Black Caucus got involved in the 21 Savage case by writing a letter to the ICE director, while BAJI and its partners created a huge petition campaign. All of these efforts not only helped 21 Savage but created a tighter coalition between black immigration organizations and black politicians to oppose the racist, no-tolerance immigration policy of the Trump Administration. Hopefully these coalitions will bring more attention to black immigration in these times when past immigration gains , including legitimate asylum claims, are being reversed. America is a nation of immigrants, and although Africans were the original “unwilling immigrants” through the slave trade, contemporary and African and African diaspora immigrants today are caught in a racist immigration morass in the era of Trump.

By Halifu Osumare

•

September 18, 2018

On September 5, 2017 Attorney General Jeff Sessions delivered a speech rescinding the five-year old Obama enacted Executive Order called the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA. This policy reversal reopened a historical U.S. debate about immigration and who is a real American. Rescinding DACA affects approximately 800,000 immigrants who had been temporarily relieved of fear of deportation as children born abroad, brought to the U.S. illegally, and came of age here. Most so-called “Dreamers” are productive Americans, educated, and contributing to the U.S. economy. Now the government will stop accepting new applications immediately, and allow current recipients with permits expiring before March 5, 2018 to apply for a two-year renewal before October 5, 2019. Trump has sent mixed-messages about Dreamers by tweeting, “We will resolve the DACA issue with heart and compassion—but through the lawful democratic process,” and mandating it to Congress to find a solution. Democrats, some Republicans, prominent business leaders, and grassroots immigration activists have all lambasted the rescinding of DACA. On September 5, 2017 Attorney General Jeff Sessions delivered a speech rescinding the five-year old Obama enacted Executive Order called the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals, or DACA. This policy reversal reopened a historical U.S. debate about immigration and who is a real American. Rescinding DACA affects approximately 800,000 immigrants who had been temporarily relieved of fear of deportation as children born abroad, brought to the U.S. illegally, and came of age here. Most so-called “Dreamers” are productive Americans, educated, and contributing to the U.S. economy. Now the government will stop accepting new applications immediately, and allow current recipients with permits expiring before March 5, 2018 to apply for a two-year renewal before October 5, 2019. Trump has sent mixed-messages about Dreamers by tweeting, “We will resolve the DACA issue with heart and compassion—but through the lawful democratic process,” and mandating it to Congress to find a solution. Democrats, some Republicans, prominent business leaders, and grassroots immigration activists have all lambasted the rescinding of DACA. How does this new policy affect the black communities across the nation, and what should be our collective response? Sessions, in his official announcement, stated one argument that has long resonated with some African Americans: Dreamers have “denied jobs to hundreds of thousands of Americans by allowing those same illegal aliens to take those jobs.” As often low-wage earners, African Americans have periodically complained that Mexican immigrants were replacing them in the work force. However, a June 2013 study published by the American Immigration Council analyzed comprehensive U.S. census data indicating that, “Immigration from Latin America improves wages and job opportunities for African Americans.” Rescinding DACA is not only cold-hearted and unfair on a human level, but will actually harm the U.S. economy, which affects everyone. The study also positioned their findings in a larger context: “To the extent that there really is a “black-brown” divide, it is rooted in politics and perception—not economics.” Examining immigration historically, it becomes not just a political issue, but also a racial one. African Americans joining the anti-DACA camp participate in the unfair treatment of potentially productive American citizens, who have only known the U.S. as home, and also ignore the historical racial undertones of past anti-immigrant policies. African American historian Jelani Cobb, in a September 5 The New Yorker article, said that the Trump administration ultimately wants to enact a Reforming American Immigration for a Strong Economy (RAISE) law, which “will slash legal immigration by fifty percent, and prioritize highly skilled English speakers among those who are allowed to immigrate.” This policy would reinforce his “Make America Great Again” demagoguery that attempts to take us back to a previous era where real Americans are seen as white. It was the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 that, according to Cobb, “eliminated the racialist immigration quotas that were set by the Immigration Act of 1924.” It is no coincident that a fairer immigration policy emerged during the Civil Rights era. Black rights and those of other people of color have always been inextricably linked to how the U.S. power structure has historically viewed who has the right to be a full citizen. Today we see a resurgence of white supremacy, with an emboldened public KKK and Neo-Nazis movement. Previous racist U.S. immigration policies actually inspired Adolf Hitler, as well as the architects of South African apartheid. Blacks, as the quintessential “Other,” should always recognize racializing arguments as they resurface in new guises, and work with other communities of color to defeat racism in all its forms, including racist immigration policies. Immigration is not a Mexico/U.S. problem, but is a multicultural issue, with DACA affecting immigrants from all nations, including black ones. A 2017 Center for American Progress survey of undocumented Americans by race listed 3.5% as Asian, 1.7% as white, and 1.1% as black. Although 92.6% are Hispanic/Latino, the seemly small percentage of black immigrants from Africa and the Caribbean represent over 12,000 people. Black illegal immigrants have felt so left out of the debate, that they founded their own organization called UndocuBlack Network in January 2016 to: 1) Blackify this country’s understanding of the undocumented population, and 2) facilitate access to resources for the Black undocumented community. Their website (http://undocublack.org) reads: “Ultimately, our vision is to have truly inclusive immigrant rights and racial justice movements that advocate for the rights of black undocumented individuals.” Co-Founder Jonathan Hayes-Green has argued articulately about the plight of undocumented black immigrants, appearing on Joy Reid’s AM Joy MSNBC cable television show. African-American scholar and Baptist minister Dr. Michael Eric Dyson has featured the National Action Network’s “Support the Fight to #Defend DACA” movement, on his twitter feed, stating “Over 12, 000 DACA recipients come from Jamaica, Trinidad & Tobago, and Nigeria. Prominent black leaders like Reed and Dyson are creating awareness of U.S. immigration policy and race in relation to black folks. As we face a resurgence of white supremacy, the KKK, and Nazism in the U.S., do not be duped by the stereotype of DACA and illegal immigrants as solely a Mexican issue. It is about who defines America. Trump’s mantra of “Make America Great Again” is a smokescreen for taking us back to an era when “blacks, Jews, Catholics and immigrants” were seen as degenerative forces destroying the white race. As Trump has put the ball in the court of Congress, the black community must urge them to make DACA a definitive law, and fight against racism and xenophobia in all its forms. Halifu Osumare, Ph.D.

By Halifu Osumare

•

December 3, 2017

“In The Eye of the Storm” Choreographer – Halifu Osumare Assistant to Choreographer – Ayo Walker Music – Delasi Nunana, Abbilona & Tambor Yoruba, Kathy Raimey, Kem Dancers – Oya – Ayo Walker The Community – Lance Casey, Miguel Forbes, Brianna James, Windy Kahana, Leanne Ruiz, Christopher Salango, Nimat Laila Shabazz We are in the eye of a national and international storm, and the crisis can only be survived in community with others. The forces causing the storm are external and internal to the community, and survival means growing spiritually. Oya is the Yoruba warrior deity of the Winds of Change, and with her husband Shango she promotes social justice. Oya brings the storm but also shows the community the way out, and as a result people grow. This dance is dedicated to Oya-Yansa. Performance – Pushfest 10/22/17 Videography – Loren Robertson Productions – lorenrobertson.com